In the corner of a train station there was a service track where mechanics repaired train cars. A young mechanic was working on a locomotive when an old man approached him.

“What are you working on?” the old man asked.

“Engine. We’re making it faster,” the mechanic responded without looking up from his tools.

“Why do you want it to be faster?”

The mechanic was puzzled. “With the new engine, the train will get there in half the time. A forty minute ride will now be just twenty.”

“That doesn’t sound like much of an improvement,” the old man said. “I don’t want to get there in half the time — I like riding the train.”

“Think of all the time it will save people,” said the mechanic.

“What will they do when they get there 20 minutes earlier?”

“They’ll be able to get to their final destination quicker.”

“And what will they do there?” the old man asked.

“I don’t know. Read the paper, have a coffee, do some work, talk to a friend.”

“Why don’t they just do all those things on the train?” the old man asked. The mechanic paused for a moment, shrugged, and leaned back over the engine. Then a loud train whistle blew, and the old man said goodbye and walked off to board his train.

When the young mechanic finished his new engine, the train did indeed get there in half the time. His company estimated it would save travelers 10,000 hours a month, and they gave the young mechanic a raise.

The old man now bought 3 tickets for each of his train trips — there, back, and there again. It was more expensive, true, but at least now he had more time to look out the window of the train as it rolled through the countryside.

There’s been a tension growing within me for the last several years. I started college interested in politics and foreign policy, but became captivated by the power and speed programming offered. Making my first website that people actually used (our college radio show’s live Q&A site) was intoxicating, and after graduation, I found myself in San Francisco working as a software engineer.

San Francisco tech culture worships scale and optimization. The biggest companies in the world are here, running technology at a scale that would have scalded the eyebrows of engineers 20 years ago. Just formed companies are expected to be worth billions in just a few years or are sold to the tech scrapyard to be stripped for parts. The number of people here making six figures to optimize some huge process like a sales funnel or recommendation algorithm is staggering.

This isn’t just confined to work. Intense rent pressure makes housing a colossal optimization problem, with multi-year efforts to buy a house and apartments that get six applicants the day they’re listed for rent. There’s an overwhelmingly endless dating pool of young people cycling in and out of the city — I know people who have spreadsheets where they rate each of their dozens of dates on a range of factors to determine how they stack up against one another. Even doing good can be hyper-optimized — the Bay Area is a hub for effective altruists, the utilitarian maximalists of philanthropy.

Whether I would have admitted it or not, I felt for a long time that I needed to do something important, even that I was bound to, that it was only a matter of time. Arrogance aside (forgive me my youth), it took me a long time to realize that my definition of important was largely a question of scale. To do a good thing for a few people was just that — good. But to do something that scaled a million or billion-fold was important, and that was what truly mattered. I had this sense that sooner or later I’d figure out what important thing I should do, and then it would be off to the races. But I waited and waited and found myself still stuck in one place.

A bigger paintbrush does not make a better painter. Beauty inherently defies scale and optimization; one definition of beauty could be unscalable meaning. My problem, I think, is that something within me longs for a deeper ideal, for something beautiful that goes beyond growth and efficiency as an end. The ruthless sacrifice of beauty at the altar of “bigger, faster, more”, made what I had convinced myself was truly important not feel important at all.

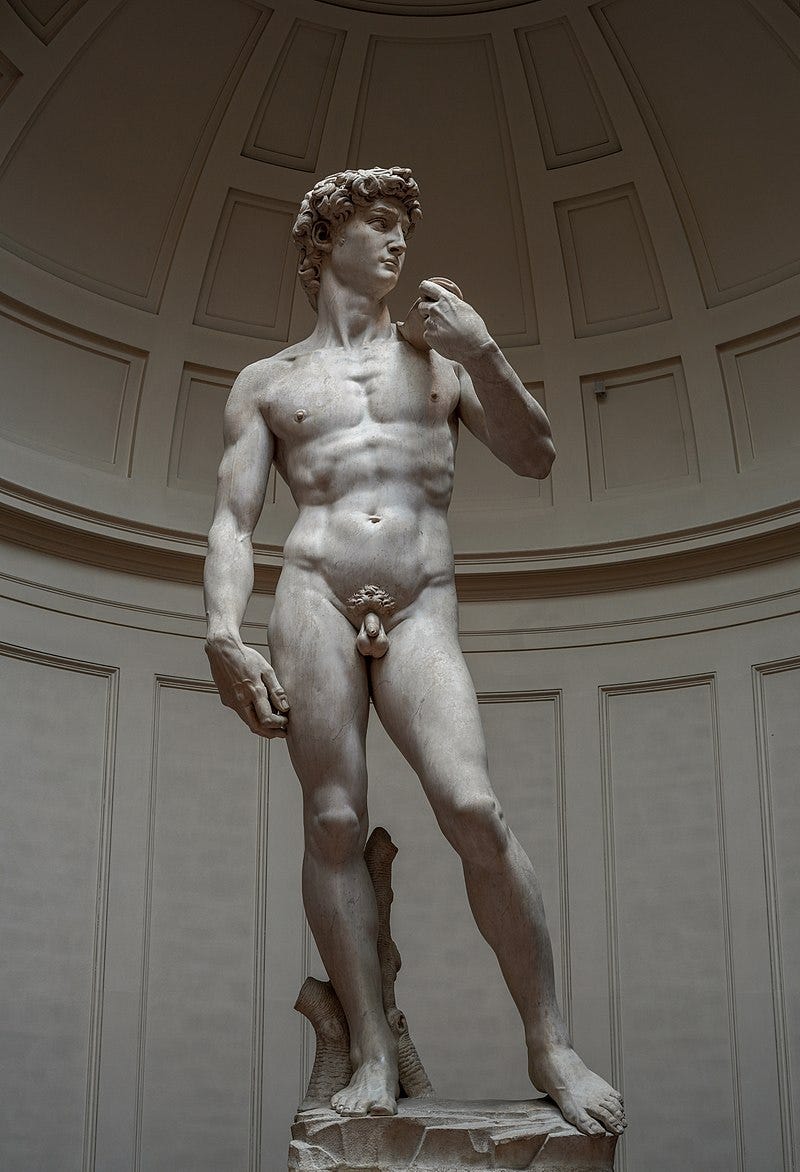

The most powerful piece of visual art I’ve ever seen was Michaelangelo’s David in Florence. It has a full room in the Galleria dell'Accademia dedicated to it, and I remember walking around the room for an hour marveling at it. The statue had a deeply meaningful effect on me, and to experience it, two things needed to happen — I needed to travel to Florence and be in the same room as this colossal piece of stone to feel its gravity and power, and Michaelangelo needed to spend two years with a vision and a chisel in hand cutting each tiny piece of stone away to expose it. That beauty, both its execution and the experience of it, can’t possibly be scaled.

You can’t optimize your way into beauty. Many of my best friends are people I would never have imagined becoming close with — people with different personalities, backgrounds, interests, values and humors have become dear friends, often to my surprise. The beautiful relationships in our life defy prediction and therefore optimization. But more importantly, to optimize them would strip them of their meaning. We cultivate beauty by following the winding path that deeply knowing someone requires, with conflict and moments of openness and shared challenges and laughter. One conversation might turn a person from an enigma to a kindred spirit, a fellow sojourner in life. Even if we could peer directly in the heart of anyone upon meeting, the peeling back of layers over time builds something beautiful that’s more than just information, understanding, or support.

What I see as important is shifting, and it hasn’t quite settled. I saw a tree last week with dozens of birdhouses on it and I had to stop and take a photo because such a silly, small thing affected me in a way that felt new. It is useless in the world of optimization and scale, but useful in a world of beauty. I thought of the foolishness of St. Francis preaching to the birds, and I realized he may not have been such a fool after all.

Scale is still good. The ability to write a piece of code (or even just an idea) and have it be useful for anyone anywhere is still magic. Optimization is still good. To take what is and improve upon it is a core part of being human, an Edenic imperative to work the existing ground. But scale and optimization are no organizing principles for a life of meaning. Scale without beauty is a Tower of Babel, reaching ever upwards to the heavens to make yourself a name and missing all the wonder of the world as a result. Without the beauty of the small, slow, and impractical things of life, all of our efficiency is for nothing, leaving us wanting more.

“Life is not a problem to be solved but a reality to be experienced,” said Kierkegaard. Life treated as an optimization problem is unsolvable, and the times I’ve tried to do so have pulled me apart with tension between a mind that seeks the important and a soul that perceives without words that beauty is crucial, that life dries up without it. I am slowly learning to see beauty in all its forms — a well-cooked meal, a hike through the woods, a song shared with friends, an elegant mathematical proof, a vulnerable moment between parent and child — as truly important, worthy of my time and attention in a world where I’m continually pulled by the current of the bigger, the faster, and the new.